Terror of the northwest passage

Capt. Sir John Franklin’s ships froze in place as winter petrified the waters around them. The cold and violent sea snapped stiff and thunderous. Pressure ridges burst icy artifacts into the sky, pale as void in the endless night. One hundred twenty-nine men waited below deck, shivering all winter beneath the frozen surface of the Arctic Ocean.

When summer came, the ice did not melt. The constant shining of the Arctic sun brought no sign of open water or wildlife. If this were the fabled Northwest Passage, these explorers may well have turned home.

But home was never an option for the crews of England’s HMS Terror and Erebus. A second summer came and went. The ice never thawed. None who made the expedition were ever seen again.

Have you heard the tale of Sir John Franklin’s lost expedition? I hadn’t until I experienced “Terror,” a novel by historical fictionist Dan Simmons. He included in his book actual messages left behind by the real Franklin explorers in 1845, filling in the gaps with a gripping story of monsters, both human and supernatural.

The fate of what happened in those awesome Arctic waters some 170 years ago matters, for better or worse, to a lot of Westerners. England, you might expect, immediately saw Capt. Franklin as a hero and inscribed the phrase “Discoverer of the Northwest Passage” into statues made of him around the world.

Franklin had survived many journeys, even gaining celebrity for eating his boots on the brink of starvation on a trip to the high Arctic that resulted in 11 crew member deaths. But on his final quest, he helped make a series of bad decisions during a time of unfortunate weather, and every man in his care died in bitter isolation on the frozen sea.

Ireland likewise built monuments of Francis Crozier, the common Irish lad turned captain who led the expedition to its doom after Franklin died at sea. He, too, is posthumously called the “Discoverer of the Northwest Passage” on a plaque pinned to the front of his childhood home.

But Canada lays claim to the expedition as well. Just last year, the then Prime Minister Stephen Harper surprised the world by announcing his government — after investing millions of dollars in a search — had discovered the wreck of the HMS Erebus, well preserved on the bottom of the Arctic Ocean.

“Franklin’s ships are an important part of Canadian history,” Harper told reporters in a surprise press conference. “His expeditions … laid the foundations of Canada’s Arctic sovereignty.”

So what does an Englishman disappearing in waters that would not be called Canadian until 20 years later when the country was founded have to do with “Canada’s Arctic sovereignty?”

If you think the answer is “very little,” you may be right, but for the governors of Canada, the answer is “enough.” The chance to stoke the fires of public love for the Arctic is a step toward controlling it, and Canada is not the only country that knows it.

Russia, in 2007, planted the first flag on the North Pole. Other trips had made it to the pole long before then, but this was the first to use a submarine to stick a flag into the seafloor, where the constantly shifting sea ice doesn’t send a staked claim drifting off into the horizon.

But what do these claims really mean?

Massive military training deployments conducted by the United States, Canada, Norway, Russia, and other northern nations often pass beneath the public’s radar. They happen because nobody knows who owns the Arctic — or maybe because everybody knows it doesn’t matter what anybody knows; apparently, sunken ships and unseen flags are legitimate factors in the international debate over Arctic sovereignty.

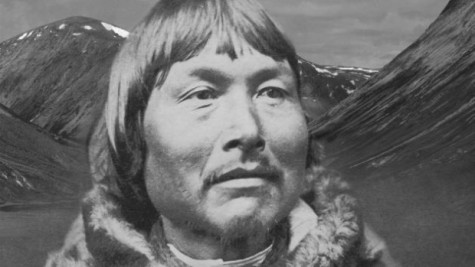

In Simmons’ imagining of Franklin’s lost expedition, one crew member survives. Crozier — committed to the throes of Arctic adventure, human love, and divine responsibility — finds home on the frozen landscape with Silence, the speechless Inuit mother of his children.

Years after leaving his Western life behind in the frozen hull of the motionless Terror, Crozier finds the ship again, still frozen in the ravaged ocean. Steel bayonets hang by the hundreds in the hull. Books fill the captain’s library. Ghosts haunt the grains of wood in every room.

The metal on board would have made Crozier’s Inuit companions incredibly wealthy, “undisputed lords of the Arctic” in Simmons’ words. But the things in the ship were poisoned with a terror as deep as the night sky. Together, Crozier and a couple Inuit built a fire. As one, they watched it burn. Alone, the Terror sank.

Then Crozier, turning from the crackling embers of his former life, remembered his new name — Taliriktug — and found it in himself to reconcile the two. Westerner as Inuit; terror as love; death as life.

If someone could have told Franklin that in 2015 — the warmest year in recorded human history — the Northwest Passage would be navigable in summer with nothing more than the abundant greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and stronger ice-breaking ships, I wonder if he would laugh or cry.

He may have been the kind of guy all for planting flags in far-off places, and it’s my impression he’d enjoy reveling over all the statues still standing in his honor. But I have to think even he’d be terrified of what has come to be.

Above the Arctic circle, ice melts and militaries gather. Eating our boots now will only make our walk off the plank more painful.

Billy Beaton is a contributor for The Dakota Student. He can be reached at [email protected]