Abe the Eskimo is in the Berlin Zoo

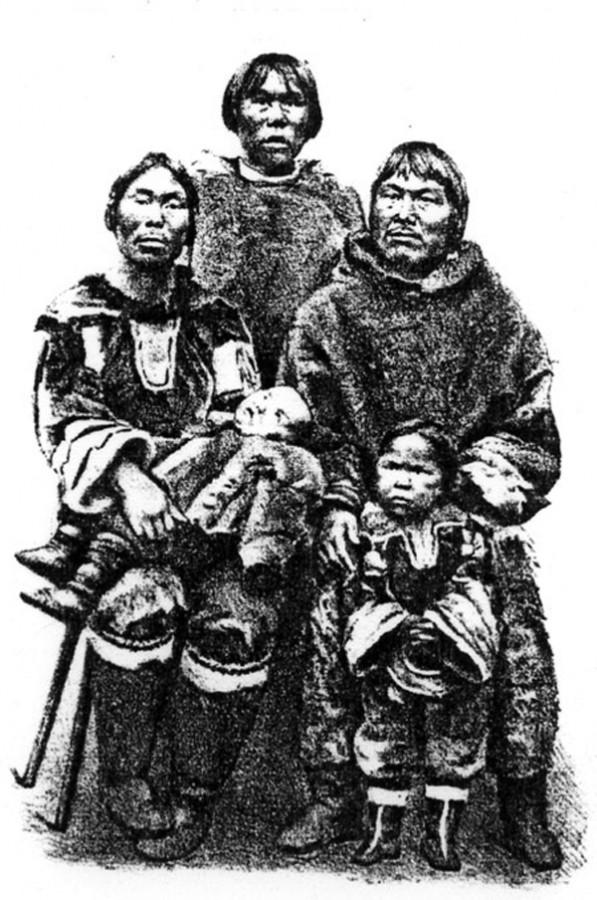

Eskimo Abe and his family posing for a photo. Photo courtesy of wikipedia.org

Several thousand faces watched, some with smiles, some with shock, as Abe the Eskimo kneeled to bury his kin.

From the concrete bleachers, they watched him prepare the burial site with his wife and friends. They saw the girl’s blanketed frame lowered into the cold December ground. When the hole was filled, trumpets rose behind the crowd to usher them away. The voices vanished. The show was over.

It was his first time in Europe — the first time almost anyone from his Inuit village in Greenland had traveled so far from the Arctic. He had a once-in-a-lifetime chance to see the world and earn money for his family in the presence of curious westerners.

He said yes and left, despite the objections from the Moravian missionaries that had converted his family to Christianity and that traded with his village in the north. He was curious, too. He had things to learn of the natural world and of his spiritual truth.

But now his friend’s daughter would not return from Germany alive. He wondered if they should have stayed home.

It was almost Christmas in Berlin.

In the 1800s, many American and European zoos sponsored “Eskimo Exhibits,” which are exactly what they sound like: performances by native people exploited by privileged businessmen to get money out of misinformed zoogoers.

Perhaps it was the fact these exhibitions took place in the same facility where wild animals are locked in cages, but German ticket holders were amazed at the intelligence of the native family — especially Abe, the father, who played folk tunes on the violin and sang along in German.

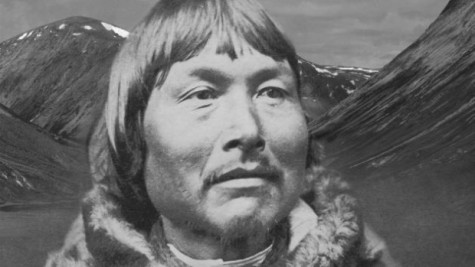

“There were so many requests, there was no way to please them all,” Abe wrote in his diary. “Even if I’m not a perfect player, they don’t mind.”

In a podcast by batteryradio.com a historian says, “I think it would have been no less astounding (the the Europeans of the time) than if the polar bears had picked up the violins and started singing in German.”

What westerners expected from Abe was nearly the opposite of what he expected from them.

“Some make fun of us, but their souls are also to be laughed at,” Abe wrote.

One day, an important dignitary from the German court came to one of the Inuit’s exhibitions at the zoological gardens.

When the gate to the natives’ enclosure was opened to allow the VIP guests a closer look, thousands of zoogoers stormed the small hut in which the Inuit were housed.

The fence was trampled by visitors clamoring for an Inuit souvenir. Police could not disperse the crowd, and the natives had to lock themselves in their hut to prevent from being torn to pieces by the excited mob.

“Since our two masters could not achieve anything, they came to me and sent me to drive (the crowd) out,” Abe wrote in his diary. “So I did what I could. Taking my whip and harpoon, I made myself terrible.”

It is hard to know how Abe must have felt, being forced to whip unruly crowds of noisy westerners he had so looked forward to seeing. It was certainly not the Europe he had anticipated — not the clean, prosperous, organized, highly religious civilization he imagined the Moravians had come from.

He endured ridicule day-in and day-out from ignorant masses “horrified” at his ability to rebuke the comments of cynical passersby in both English and German. And perhaps it is no wonder he faced such racism from the paying rabble — especially when the science of the time is consulted.

The foremost physician in Germany and founder of the Ethnological Society paid Abe and his family a visit while he was in Berlin. After examining the natives, the honored physician gave a presentation to his scientific colleagues, many of whom would help perpetuate a deep-seeded scientific racism that plagued researchers of the time.

“Nothing has more forcefully strengthened the impression that the Eskimos are of a lower race, than their clumsiness in using numbers,” the professor proclaimed in his talk.

Another giveaway of their savageness, he recalled, was how one Inuit woman reacted when he tried to measure the size of her breasts without her consent.

“She jumped from one corner to the other and was screaming with a crying voice,” he told the scientific community. “Her ugly face looked dark red, the eyes were glowing, there was a bit of foam at the mouth. To sum it up, it was a highly disgusting sight.”

Newspapers, too, used the exhibitions to stir their own spectacle.

“The Eskimos at the zoological gardens are representatives of a rapidly dying people,” wrote one newspaper in 1880. “You can almost predict the year when the people of the north will be gone.”

This reflects the widely held belief — supported by some of the world’s best scientists — that Inuit were actually of a more primitive ancestry than whites and were effectively more like cavemen than civilized human beings.

There is more to the story of Abe’s journey, and I will relate the details of its end in next week’s issue of The Dakota Student.

In the meantime, I wonder how we may see similarities between how western culture absorbed Abe’s tale and how it understands polar bear conservation today. A baby polar bear born in the same Berlin Zoo 125 years after Abe was on display generated an estimated $140 million in merchandise, branding and ticket sales until it had a stroke and drowned in front of heartbroken spectators, who had come to watch a confused bear swim circles in a cage one millionth the size of its natural home range.

We may not be as different from our western ancestors as we may hope to be after all.

Billy Beaton is the video editor for The Dakota Student. He can be reached at [email protected]