Why wildlife matters

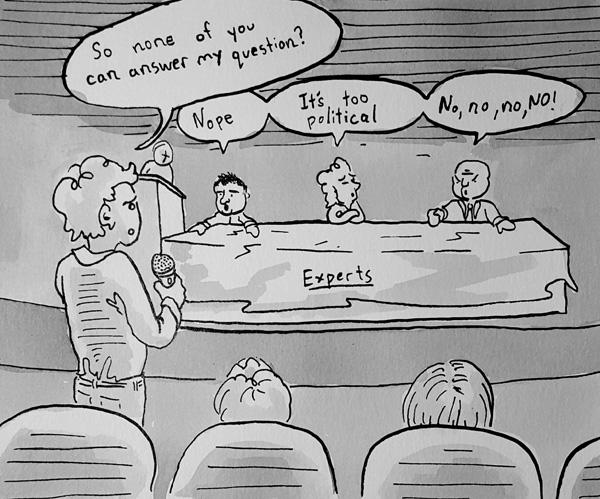

Comic by Bill Rerick/ The Dakota Student

There were hundreds of researchers in the room. They had driven in vans or flown in planes from the ends of North America to the place where two rivers meet in Winnipeg, with one question: Why does wildlife matter?

The most distinguished and promising conservation scientists took the stage to answer. Students listened and scribbled notes. Tenured professors sipped on coffee. Somebody paid a photographer to snap photos.

I’d never been to such a large conference about wildlife, and I was pleasantly surprised to see as many young people as I did. We made friends in the opening keynote who we ended up seeing almost every day. Only a few minutes into our week in Winnipeg, we were ready to see how the experts within our field felt about the state of the world and our responsibilities to protect it.

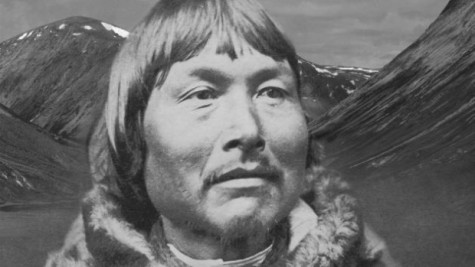

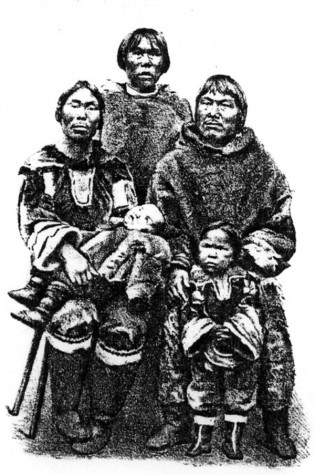

I had come with questions about polar bears. Since reading into the species’ “threatened” listing on the Endangered Species Act, I’ve become fascinated about how people see the polar bear as iconizing the relationship between western desire, indigenous right and the spirit of nature.

It was just my luck on the second day to find myself sitting next to one of the world’s leading polar bear researchers on the bus back to the hotel. I chatted him up, and he invited me to attend his presentation the next day. I did just that.

I thoroughly enjoyed his talk and had lots of questions by the time he finished. I raised my hand and asked the first: How had a previous government effort I had read about influenced his research?

“I’m not going to answer that question,” he said after a moment. “It’s a political question.”

Immediately, another leading polar bear researcher in the audience raised his hand. The man on stage asked, “Would you like to answer that question?”

“Oh, no, no, no,” he said. He had another question. And for some undefined reason it was more answerable than mine.

To be clear, my question was partly political in nature. But if I’ve learned anything pouring over hundreds of pages of government documents, science papers and news articles about polar bear conservation, politics cannot be separated from the socioeconomic context in which the work of every scientist at the conference is done.

And if I can’t ask the world’s leading experts in polar bear conservation about anything outside the focus of their abstracts, then where in this world am I to go? (I certainly could have remained home and kept finding all I could online).

I do understand why he didn’t want to answer my question, and I appreciate how sincerely he explained why he wouldn’t. But as I leaned back in my chair empty-handed, it sunk in how lost we are.

A polar bear expert couldn’t give me his professional opinion on polar bear conservation, and a room full of other experts thought that was totally fine. Isn’t that as bad as the nightmares we have of the public misunderstanding how science is done? How can we hope to help them learn if we can’t even talk openly about it between each other, especially the younger people?

New friends we’d made from Mississippi wanted to meet up; their conference experience was proving to be different from what they expected.

We made it to the King’s Head pub as the Justin Trudeau election results came in on TV. We sat around a circle of drinks as locals and American conference-goers whistled and booed throughout Prime Minister Harper’s farewell address.

Returning from the bar, I dropped two crumpled receipts onto the table, and for a moment we all seemed rather distant staring into the reflective plastic of that wasted paper, printed with the compliant understanding of both consumer and cashier that it would be thrown away without the slightest use.

We remembered the plastic plates and needless cocktail napkins thrown away at reception after reception at the conference — we spoke of our thoughts on the piles of artificially fresh fruit and discarded plastic cups burned through at breakfast.

Had we traveled so far to learn about conservation that we didn’t realize our catering bill would have looked the same had we been a part of a conference for climate change deniers?

Of course, again, I am not surprised or offended at anyone’s demeanor at the conference. We got along as best as human beings could, as well as our culture would.

But we are some 1,500 people who actually have a collective say in deciding how science is done. Why aren’t we genuinely freaking out? Why aren’t we throwing things against the walls and gathering in bands to do something about what we see?

Instead, when we gather in the hundreds to commiserate, we tend to neglect the larger calling that had first brought us together. We eat cheap deli meat with disposable knives. We don’t talk about politics with publicly funded researchers in public.

Why do wildlife matter? I don’t know. I don’t think anyone who does really does.

But when did we decide humans had no part in it? That there are wild things, and then there’s us, apart, free to make as much plastic trash as possible while waving the banner of conservation?

I consumed as much processed cheese and imported coffee as anyone. I threw away enough napkin squares and program pamphlets to build an arc. I’m Peter accusing Paul of being two-faced.

But if even the alleged masterminds of conservation can be coolly aware of the massive human impact on the earth while chatting nonchalantly about whitetail deer movement over microwaved spring rolls, we may be in trouble.

Wildlife matters so long as we matter. Can we be wasteful and still succeed in conservation? Can we shut each other out of discussion and still learn what we need to pass on in our legacy?

You could ask me, but I feel as wild as the great white bears on the freezing Hudson Bay or the ones behind glass in San Diego. I wonder which might matter more, or if the opinion of each would be disregarded anyway.

Billy Beaton is the video editor for The Dakota Student.

He can be reached at [email protected]