Abe the Eskimo’s last days

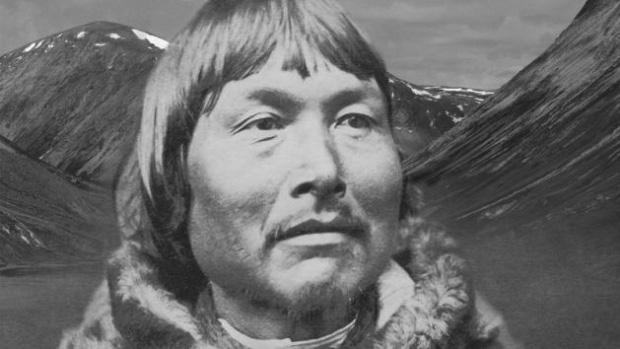

Inuit Abraham (Abe) Ulrikab photographed before leaving for the Berlin Zoo. Photo courtesy of cbc.ca

The media exacerbated the myth that Inuit people were of a more primitive ancestry than whites, and a slow disease crept from the polluted city streets into the blood of the Inuit.

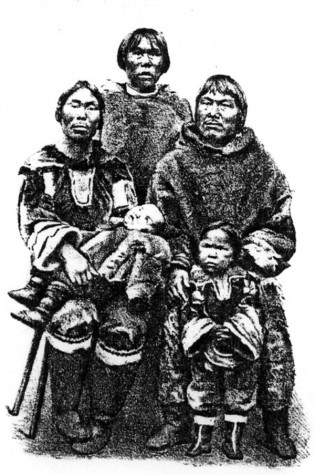

When the 15-year-old daughter of Terrianiak, Abe’s neighbor, died suddenly in Frankfurt, the atmosphere of the adventure soured. When the girl’s mother also died two weeks later, it darkened into a hell that would consume them all: smallpox.

Johan Jacobsen, the European who had recruited the Inuit in Greenland, had simply forgotten to get them vaccinated, as he was required by German law at the time to do. He had brought other Greenlanders to the west and had them vaccinated in the past. His mistake on this trip resulted in each of them suffering long, excruciating deaths.

“I feel directly responsible for these people,” he wrote in his journal, as all eight Inuit on the trip fell ill one after another.

There must have been a moment after the death of his friends and 3-year-old daughter when Abe realized they were all doomed to die.

“Oh my dear teacher, all day we cry that our sins will be taken away by Jesus,” Abe wrote in his last days on Earth. “We do not doubt that the Lord will hear us.”

After his wife and daughter died, Terrianiak, formerly a shaman from their village in Greenland, “asked for a robe so he can strangle himself for he (was) suffering terribly.”

Abe’s wife was the last to die, as arrangements were made to send the Inuit’s pay to their families in Greenland. When the Moravian Christians at Hebron Mission Station in the Greenlandic north learned of their disciples’ deaths, they responded with something less than complete sincerity.

“We are glad that finally the situation became so serious that Abraham was able to see his mistake and feel ashamed of it,” they said. “If they had come back healthy and rich, a craving to go to Europe to get rich quick would have become endemic with the other Eskimos.”

As that would be bad for the Moravians’ trading business in the Inuit village, it’s easier to understand their “gladness” in hearing the tragic news.

I have not read if the natives’ payment ever made it to their families in Greenland, but the gear they brought with them to Europe was certainly looted. Even the skullcap of Pango, Terrianiak’s wife, was stolen by the sailor Jacobsen who “stuffed” it into his suitcase after her autopsy.

Later, he had offered the artifact to a professor in Paris who would “get rid of it” for him.

“The professor accepted it gladly,” Jacobsen wrote, “put it under his topcoat, and marched off with it.”

Anyone suggesting native persons spend time in a zoo exhibit today would be rejected by the majority culture. Is that because we wouldn’t dare let human rights be violated? An exhibit like that today would simply not sell enough tickets to the more informed global audience of 2015.

“I am a poor man who is dust,” Abe wrote in his diary, as death flooded his body.

But dust is worthless. The skull of a bonafide Eskimo might at least fetch a greedy sailor a few bucks in the nearest back alley.

Billy Beaton is the video editor for The Dakota Student. He can be reached at [email protected]