Mourning Knut the polar bear’s death

Faces and clicking cameras chattered on the edges of his exhibit as always.

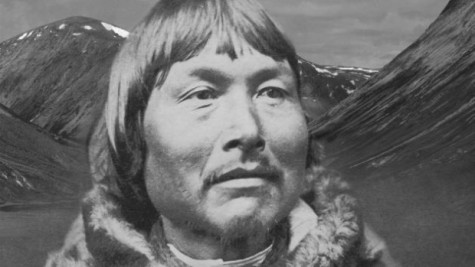

Knut the polar bear, Germany’s favorite captive animal and the world’s symbol of conservation, stood in his enclosure.

The morning poured empty sunlight over the concrete rails and against the backs of onlookers filming while the bear began to spin in a slow, deliberate circle.

He balanced on the rocks near the edge of a dark pool. Voices laughed and wondered what the bear was thinking. Most remained silent and snapped photos.

Knut continued to spin, then drag a hind leg, looking as if he had lost control of his limbs or mind. He jaw began to snap. His head twitched in horrible directions. Finally, he stopped and faced the crowd, stretched his body toward the sky in a seizing mess, and slipped backward into the still waters of the pool.

“Hilfe!” someone shouts. Children scream. Knut is gone.

This was how the superstar product of the Berlin Zoo died — not with a whimper, but a muffled splash.

To the zoo’s investors, it meant big change.

By the time he had reached the age of 2, The New York Times reports, Knut had earned $8.6 million in ticket sales and merchandise — from “plush toy Knuts for nearly $30 and Knut baby videos for the same.”

The zoo even registered “Knut” as an official legal trademark.

To Knut Krazies all over the world, it was heartbreak.

Below the YouTube video of Knut’s official theme song, for example, some comments read today, “I’m crying so hard!!!!!!!!!!!! (sic)” and “R.I.P. KNUT BIT I LOVE YOU I HOPE YOU COME ALIVE AGAIN (sic).”

I should point out that the outlying comment: “This is crap” has three likes.

In reading through all 108 articles in the New York Times archive for a class paper, I assumed Knut’s death would be the last I’d hear of him. Perhaps on the 10th anniversary of his death, papers might care to mention Knut in passing (likely cynically, in a recap of other “washed up” celebrity animals).

But I was wrong.

In April 2011, the Times published “For Mourners of Knut, a Stuffed Bear Just Won’t Do.”

Following the pattern of most all of the news coverage Knut received, the paper didn’t report on the death for American audiences until a month after his death, when a familiar conflict could be drawn between “sides” of the story.

On one end, the heartless zoo hoping to keep Knut’s remains on display. On the other, the bleeding heart Knut fanatics demanding his burial, in what the Times reporter called “the battle over Knut’s remains.”

Words like these sell gripping images and get more clicks online. But they may not paint in the most honest picture. They do, no doubt, keep the story alive.

And it just keeps coming.

In January 2012, there’s more Knut news in the Times with the headline, “In Death as in Life, Knut the Polar Bear Demands Attention.”

To kickoff the article, the reporter makes a valid observation: “Whether one bear needs three memorials in a single city is debatable.” But if you think supporters wouldn’t raise $19,000 to build a bronze statue called “Knut — The Dreamer,” then you haven’t realized that Knut was no mere bear.

Much like the great bears in the northern sky, Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, Knut came to stand for something far greater than what he once was.

The statue was actually constructed and it is still visited by visitors worldwide today. Whether such a donation would best be spent on actually conserving polar bears in the wild is also debateable.

The zoo director, who once complained of all the “silly presents” Knut’s mourners left as his first memorial, seemed passionate about supporting the statue.

“For a human, you have to be dead for five years before you can have a street or a square named after you,” the Times reported him saying. “I think a year for an animal is reasonable.”

What keeps the story alive, keeps the money flowing. That may be an unfair summary of the decision to build, but the next time Knut makes a Times headline, a European court ruled a British company could not “sell merchandise under the name ‘Knut — Der Eisbar’” since it “was too similar to the registered trademark ‘Knud,’ which the zoo already (held).”

To the very end, we’re reminded that money makes the industry through which we met Knut. Without it, I’d never have watched a 50-second video of a polar bear drowning in a depressing stagnant pond in front of hundreds of mortified zoo-goers

But also, Knut’s last mention in the New York Times tells us, we’d lack a specific insight into one area of veterinary medicine.

Just this summer in 2015, the Times told Americans of a study that showed the long-awaited results of Knut’s updated autopsy. It turns out, some researchers found, Knut “had an autoimmune disease that attacks the brain…and was thought to affect only humans.”

Billy Beaton is the video editor for The Dakota Student. He can be reached at [email protected]