Hunting for one’s greater self

Part Four of The Bears That Zeus Made

Wet, steamy breath billows from the mouth of the dying polar bear. It lays partially on its side, heavy head resting on the jagged sea ice blinking at glints of light glowing deep within the frozen crystals of the morning air. Its powerful limbs now made to rest; its dripping nose now smelling death.

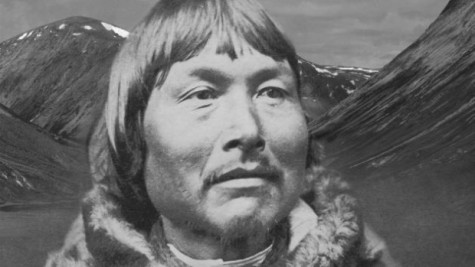

A man approaches cautiously.

Others walk in a circle, tightening slowly around the felled beast. Dogs jump on chains and howl their excitement.

The sun sets early in the winter cold and stretches the creature’s shadow long and patiently against ephemeral snow drifts.

Before the white predator dies, it raises its mighty face once more and sniffs the sky.

The men will never know what the 1,000 pound animal thought as the last of its warmth slipped between its teeth and followed the bitter wind growling across the frozen sea.

But the men know something else — the secret to a relationship sustained for centuries, the reason there are any eyes to open on the Arctic at all.

For a people so intensely dependent on the environment’s graces, survival is only possible — or worthwhile — for those who define themselves not by the boundary of their skin, but by the light of the melting horizons, the depths of the salty ocean, and all the beating hearts beyond.

From this perspective, the dogs don’t sound fearful, the hunter doesn’t kill out of hate, and the bear does not die at all.

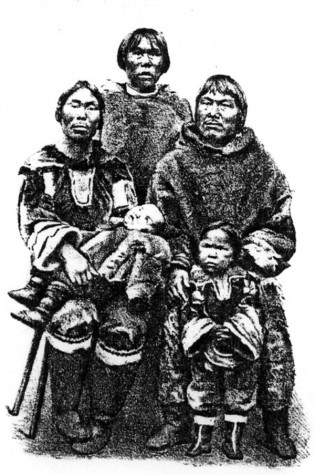

Much of indigenous tradition sees wildlife as inseparable from the land, and nowhere is a distinction made to say that the Inuit (which translates to “the people”) are not themselves as wild as any other life in the tundra.

All life, and all landscapes that allow it to grow, arise together. Seas freeze and flow. Sunlight comes and goes. Life is, then isn’t — then is again inexplicably.

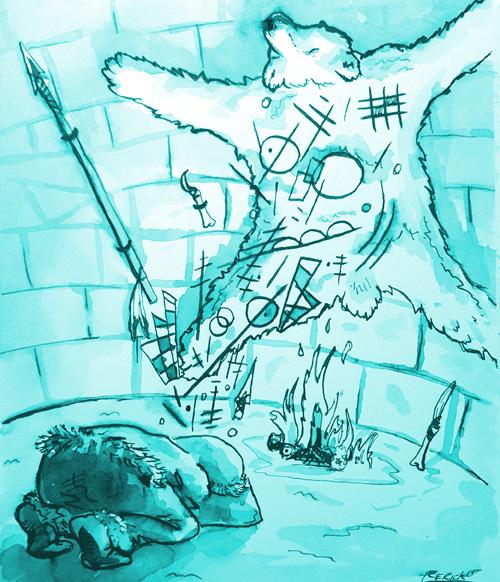

When traditional Inuit kill a polar bear, an ancient ritual begins to keep the acts of the people in line with their philosophy of the greater self common to all things, living or not.

Not an ounce of the bear’s remains will be wasted.

Its meat will feed a family. Its fur will warm them. Its bones are weapons. Its claws are tools. Its sinews are twine. Its fat is fuel.

Once the pelt is returned to camp, it is ceremoniously hung in the home of the hunter who brought it back.

For days, the family respects the bear’s gift by leaving it gifts of their own. For a male polar bear, knives and weapons are hung with the pelt. For a female bear, needle cases and other utensils are offered.

The polar bear, adopting a human form as it enters into the afterlife, will take with it the spirits of the tools hung up for them, and if they are pleased, they will tell other bears to be killed by this man, for he loves his kill as he loves his family.

And so the greatest gift the Inuit could give the soul of a slain polar bear are the tools to hunt polar bears, since they actually see themselves bleed to death on the frozen ground each time they take a bear’s life.

The Inuit wouldn’t dream of sending a polar bear off into the spirit world without the proper tools.

The gargantuan danger posed to bears by today’s warming ocean seems as scary as any hereafter might be, but perhaps we’ll find a way to provide polar bears with what they need to cross their existential threshold and experience the uncertain journey ahead.

Billy Beaton is the video editor for The Dakota Student. He can be reached at [email protected]