Dakota Access Pipeline

Ears of corn hang at a camp near the Dakota Access Pipeline construction site.

November 8, 2016

The battle over the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline continues in Cannon Ball, N.D. Over the last week, its influence reached campus at the University of North Dakota.

Chalk messages, proclaiming “water is life” and “#noDAPL” appeared on sidewalks all over campus, to spread awareness of the ongoing protests, which reached a head Halloween weekend, when 141 protesters were arrested by police in riot gear.

The protests, which started last April, are over the route of the Dakota Access Pipeline, an 1,100 mile long, underground pipeline from northwestern North Dakota to central Illinois. The line is projected to cost $3.8 billion. The protests are occurring at the north end of Standing Rock Indian Reservation, an hour south of Bismarck, in three camps: Sacred Stone, Oceti Sakowin (named for the Great Sioux Nation) and 1851 Treaty Camp, with another Winter Camp growing as well. Members from over 300 Native tribes are residing in the camps, as well as several thousand supporters.

While the pipeline runs through treaty land granted to the tribe, and has already destroyed one archaeological site, the primary issue is the threat to the local water source.

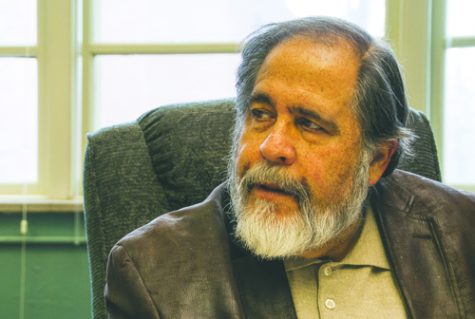

“The pipeline is someone else’s fight,” says Mark Trahant, an assistant professor at UND and a nationwide reporter. “They just don’t want it by their water sources.” Trahant has been following the ongoing protests on his website, “Trahant Reports”.

The issue isn’t just local. Standing Rock sits at the headwaters of the Missouri River, part of the largest river network in North America. An uncontained spill of the pipeline could threaten the water supply of over 18 million people.

Ironically, DAPL was originally going to be routed northeast of Bismarck, but was relocated due to fears over water source contamination.

These fears aren’t unfounded; in May 2013, the underground Pegasus pipeline ruptured in Mayflower, Arkansas, flooding a cul-de-sac with crude oil.

In January 2015, a pipeline spilled up to 50,000 gallons of crude oil into the Yellowstone River, and 6,000 people were denied tap water due to cancer-causing chemicals in the water as a result of the spill.

“The big question, in North Dakota or Montana,” Trahant said, “is what do you do when there’s 30 inches of snow and ice?”

These were the conditions present in January 2015.

In the past 12 months, the North Dakota Department of Health has recorded 26 incidents of crude oil leakage, with the largest amount being a pipeline spill of 10,000 gallons on August 21.

Meanwhile, the opposition to DAPL continues; the United Nations has criticized the United States over the issue, and a Human Rights team is investigating possible abuses against the protestors by police.

At campus, students and faculty are also getting involved; recently, Indian Studies lecturer Jaynie Parrish led a field trip to the protest sites, and student Alex Aman is planning a donation to the protestors by Thanksgiving.

A boycott of gasoline is also scheduled on Facebook for November 7th and will last for two weeks.

“Given the history of the university’s mascot debate,” Trahant said, “It would be interesting if those supporting the Fighting Sioux went out and supported the fighting Sioux.”

Connor Johnson is a staff writer for The Dakota Student. He can be reached at [email protected]