Biology Department specializes in research

Three professors share their current (and fascinating) research projects

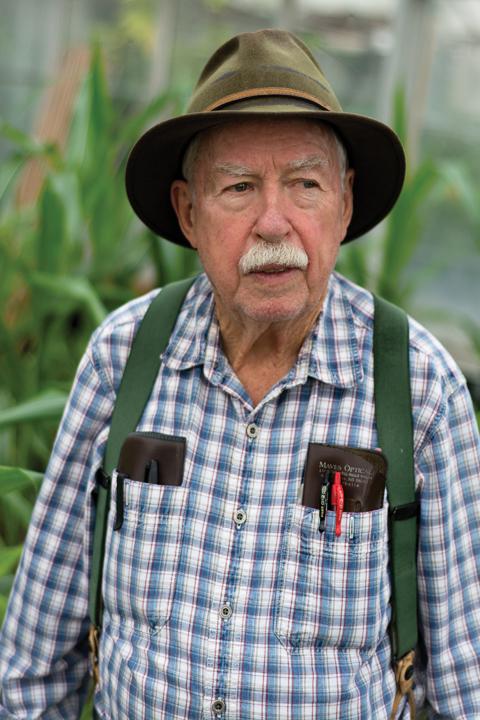

Dr. William (Bill) Sheridan has a passion for corn and for higher education. Photo by Nick Nelson/The Dakota Student.

Corn in Pacific Ocean

Chester Fritz Distinguished Professor Dr. William (Bill) Sheridan has lived a life of academia. He was born and raised in Florida and as a child became interested in plants. This interest lead him on a long and intensive path of research, teaching and service.

In 1958 Sheridan obtained his bachelors degree in agriculture and in 1960 he received his masters degree in botany, both from the University of Florida. From there he attended the University of Illinois where he received his Ph.D. in 1965.

After that he went to Yale for three years before leaving Connecticut for the University of Missouri where he resided for seven years. From that point he made his way to his current position at the University of North Dakota in 1975.

“There are two reasons I stayed in North Dakota,” Sheridan said. “One of them was because it was a good environment to continue my research on a large scale, because I was provided with quite a bit of space. And the other reason is that I like it here, I like the people very much in North Dakota and I like the university a great deal so this has been a very good place to do my work and live.”

Sheridan’s research interests are in genetics and developmental biology. He is currently doing research on how genes control reproduction in plants. Some graduate students work with Sheridan, learning how to take care of and analyze the results, among various other things.

“We grow an experimental cornfield here in town, up north of Simplot, and we grow corn there in the summer,” Sheridan said. “We also have a field that we grow in the winter and that’s out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. I go out there and work during the winter to pollinate the corn.”

With his long, academic career at numerous universities he is a strong believer in higher education.

“It is the campus experience that hopefully helps students to grow mentally, intellectually and to broaden their horizons,” Sheridan said. “The future lies in the hands of our young people who are here today. For them to vote wisely at the polling booth and provide leadership in the communities and the legislatures and in their professions, that’s so crucial for the future of the country and of the world.”

Sheridan plans to continue to teach for as long as his health holds up — taking long walks everyday to see that it does. He will continue because he has found what he loves to do and hopes that students are as fortunate as he has been to be able to do what they are passionate about.

“In the long haul, if I had any one piece of advice for students it would be to encourage you to be more serious,” Sheridan said. “Take advantage of the opportunity that you have to grow as a person when you’re a student.”

Ashley Carlson is a staff writer for The Dakota Student. She can be reached at ashley.m.carlson@my.und.edu.

Zebrafish on Cocaine

Assistant Professor of Biology Dr. Tristan Darland is a native of New Haven Connecticut, but was raised in New York City and San Diego. He began working at UND in 2005 along with his wife Diane Darland.

When he began, he was given a research position and a little lab space, but over the years, Darland began to teach classes here and for a year at Turtle Mountain Community College. He was hired by the Biology Department as a tenure track faculty in 2011.

While Darland has always been interested in science, he says that he first wanted to be a marine biologist and later a veterinarian before finally settling into his current field.

Darland’s research interests are primarily in neurodevelopment in zebrafish and neural stem cell regulation and addiction related behavior. Darland is interested in the causes of addiction — what makes some people vulnerable, but not others.

“(I use zebrafish because) they’re basically a vertebrate fruit fly,” Darland said. Meaning that you can do many genetic manipulations in them far easier than you can a mammal like a rodent.

He introduces large numbers of mutations and consequently raise families that are genetically identical except for one or two mutations. He then looks for things such as response to cocaine, finds which families are abnormal and finally looks for the disrupted gene. Presumably this will be the addiction gene.

“Early development and basic physiology is comparable between humans and fish,” Darland said. “For example, fish learn to respond to cocaine behaviorally.”

“Fish respond physiologically to cocaine similarly to mammals,” Darland said. “Their hearts beat faster and their blood vessels constrict. Presumably, the genes that are affected in fish will be conserved in humans too.”

Not only does Darland look at the genetic causes of addiction but also the environmental influences, such as early exposure to drugs during early embryonic development.

“I think it is fascinating how the brain constantly responds and adapts to environmental stimuli by developing new behaviors and strategies for obtaining the needs of the organism,” Darland said. “Unfortunately, addictive drugs subver this amazing natural phenomenon into something destructive and tragic.”

Darland is interested in applying his findings to human populations. Recently, he had a student circulate a survey to North Dakota and Minnesota born UND students. The survey scored alcohol use and asked questions that reflected the levels of certain key neurotransmitters in the brain.

He has combined that with genetic testing for genes that may pose a risk to forming addiction. Currently, he is doing the computations liking the survey and the genetic testing.

“I have addiction in my family history and so I have a personal interest,” Darland said. “Though I have to confess I kind of got into this accidentally.”

Katie Haines is a staff writer for The Dakota Student. She can be reached at katie.haines@my.und.edu.

Wildlife Enthusiast

Wildlife Ecologist and assistant professor Susan Felege has been at UND for about four years now. This Pennsylvania native was raised surrounded by nature and nature lovers.

“My motivation was mostly my upbringing,” Felege said. “We were avid hunters and with my father being involved with wildlife conservation my curiosity for learning more continued to grow.”

Her father, being a deputy wildlife conservation officer, was the one that opened up the wildlife ecology door for her. When she was 13 her father took her out banding ducks for research.

According to, birding.about.com, “Bird banding is the process of attaching a small metal or plastic band around a bird’s leg in order to identify individual birds from the band’s unique number.”

“That is when I realized what I wanted to do,” Felege said.

Felege received her undergraduate at Penn State and a Ph.D. at The University of Georgia. Her education and research has taken her all across the United States, but she knew she wanted to end up in the Dakotas.

“I’ve always loved the Dakotas,” Felege said. “It’s the Prairie Pothole Region and a hot spot for wildlife ecologists.”

The PPR is an area of the Northern Great Plains filled with midgrass and tallgrass prairies which is home of shallow wetlands known as potholes. Over half of game species duck breed there.

Although Felege isn’t specialized in a specific wildlife branch, this has helped her broaden her horizon to multiple breeds of wildlife. Some she has researched include — muskrats, waterfowl, songbirds, sharp-tailed grouse and various endangered birds.

Felege said she always has a lot of different projects going on at once. However, she really enjoys working with nesting cameras and even surveillance cameras.

“You learn so much about an animal’s behavior through hidden cameras that you wouldn’t learn any other way,” Felege said. “An animal is going to act differently when they know they’re being watched.”

Felege added that she likes “new tools and novel techniques” to advance her understanding of animals and help answer questions. Recently she has collaborated with unmanned aircraft to see a new perspective.

She also said that citizens of Grand Forks and students of UND can help by sitting at a computer and watching a live feed of wildlife from all over North Dakota.

“It is called Wildlife@Home,” Felege said. “Be a volunteer and help us out.”

Hailie Pelka is a staff writer for The Dakota Student. She can be reached at hailie.pelka@my.und.edu.