Library to discard thousands of books

Librarians and faculty grapple with what ‘outdated’ means to the humanities

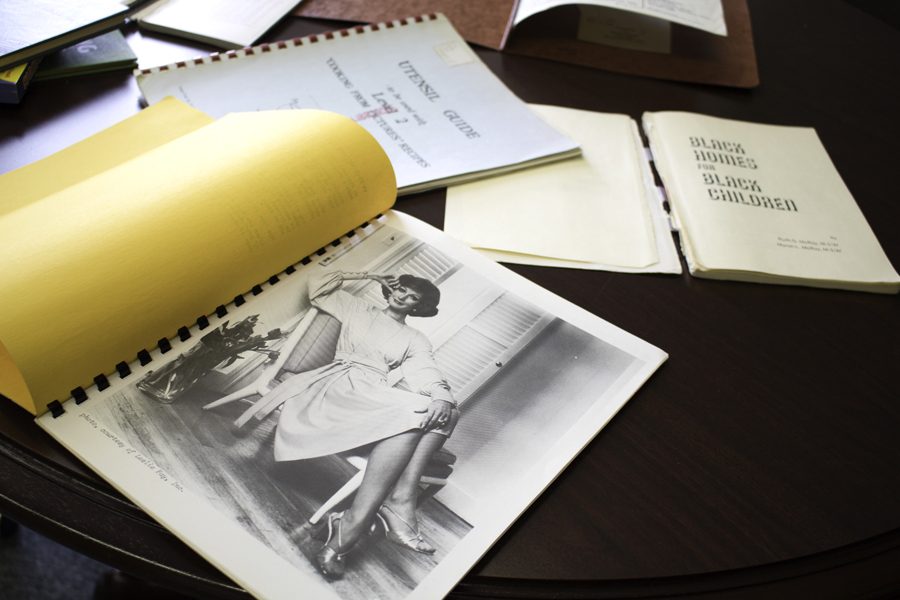

Trevor Alveshere / Dakota Student

Thousands of books are slated to be disposed of from the Chester Fritz Library in the near future.

April 8, 2018

Until a few months ago, the Chester Fritz Library still counted among its collection a 1958 edition of the book “Fabricating with Formica.”

Dean of Libraries and Information Resources Stephanie Walker says that while she’s no engineering student, she assumes Formica techniques have come a long way since Eisenhower’s presidency.

Also among the library’s collection: a CD promising 90 minutes of online time with AOL.

“They have never deaccessioned,” Walker said, referring to the university’s library. “It’s supposed to be roughly an annual or biannual process.”

Deaccessioning refers to libraries culling their collections, taking books that are out of date, in bad physical condition, or duplicate information off the shelves. Walker said the fact that UND’s library collection has never been through this process is “very unusual.”

“I’ve never heard of that happening before,” Walker said.

The Chester Fritz’s deaccessioning process began in the fall semester of 2015 as the library began to alert faculty and students about the process and began talks with the Online Computer Library Cooperative, whose Strategic Collection Services took the library’s circulation data from the last 25 years to tell them what is circulating and what isn’t.

Some subjects are seen as relatively easy to cull, like computer science and engineering, whose information must be as current as possible. The library is now in the early stages of deaccessioning books pertaining to english, history, philosophy and religion, and in these subjects, there could be more controversy over what “current” or “useful” means.

According to Walker, however, deaccession at the Chester Fritz does not necessarily mean students will never again have access to the information contained in those books.

“I think some faculty worry that everyone is going to discard willy nilly and then before you know it there won’t be anything left,” Walker said. “No, libraries have gotten together, research libraries and others, and joined a consortium called LOCKSS – Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe – and people have agreements like Harvard is the place that will always keep a print copy of x. And there’s multiple ones of all of it. So there’s backup in case Harvard gets blown away by a nor’easter or something.”

Walker stresses that in the deaccessioning process, the library has taken into account digital resources and copies available to students. However, some faculty worry that with heavy reliance on digital resources, students could miss out on vital parts of the research process.

“I am concerned that the deaccession will remove items that, while a specific case might not be made for them, would or could provide valuable insight in ways not expressed in journal sources,” Michelle Sauer, the english department’s library representative, said. “I remember during my undergraduate days that one of my favorite research techniques was ‘shelf reading,’ meaning I would go to the location of the book I had found in the card catalogue and then start reading through the books around it as well.”

Due to her experience with inter-library loans, Sauer also has concerns about availability of information that is not directly housed by UND.

“A big issue for our department is the library’s relatively recent (late 2016) decision to begin charging for some ILLs,” Sauer said. “Nearly all of us have been affected by this policy despite assurances that the requests for money would be few and far between.”

As the library representative, Sauer says the english department was informed in a March 19 meeting that the Humanities deaccessioning will begin. Faculty that have signed up to receive the list of books up for deaccessioning will be emailed the information and the list will be posted online. Faculty members can make a case for the reinstatement of the book or claim a book. However, because of state law, books that are claimed by faculty cannot be taken off university property. Once the list is released, faculty will have 30 days to review it and choose to take any of these actions.

“I hope that we will have sufficient time to read through all the entries and make appropriate responses,” Sauer said. “Surely the library staff understands that the end of the semester, heading into summer, necessitates allowing a longer time than usual to respond to such things.”

Walker said she thinks the 30-day period is long enough for the review process and that to her “it feels very long.”

Because of North Dakota laws about state property, the Chester Fritz can neither give away nor sell books they are deaccessioning to students. Most of them will be recycled either because of old book binding and glue. The only option available is the landfill.

Despite the circumstances of the Walker says she is hopeful for the future of the library. Currently, books occupy 67 percent of the physical space of the building, whereas in comparable libraries, books take up 18 percent of the space on average. Walker hopes the deaccession and ensuing building renovations will make the library a more utilized space.

“We want to have a space that belongs to the whole campus,” Walker said.

Diane Newberry is the editor-in-chief for the Dakota Student. She can be reached at [email protected].