Remembering a lost friend

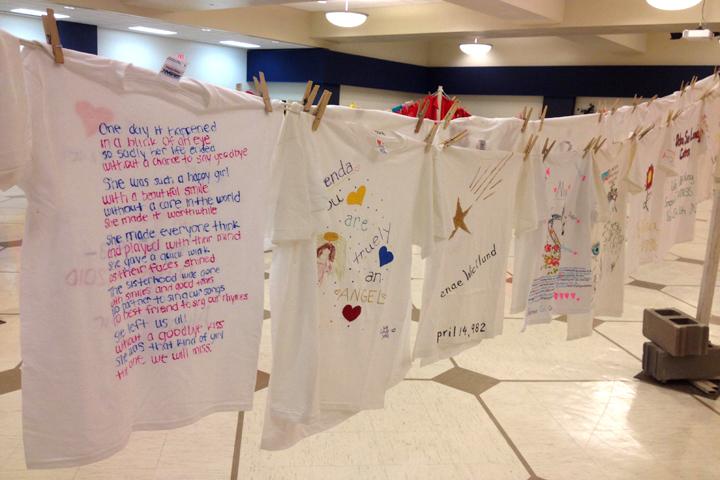

RESPECT UND’s Clothesline Project stirs memories.

UND’s Clothesline Project, which ends today at noon, in the Memorial Union Ballroom. The project comemmorates the stories of victims of familial abuse, domestic violence and sexual assault. Photo by Will Beaton/ The Dakota Student.

Upstairs in the Memorial Union, right now, UND’s Clothesline Project is on it’s last day.

For those whose shirts hang one after another in that brightly lit room, the end of the week won’t bring an end to the long process of healing.

Monday, I took some time to walk through the event, to look at the mix of pink and red and yellow and blue and orange and green and purple shirts. My eyes, however, were set on the white ones, which stood out brightly against the other hues.

The shirt I was looking for was a few rows in, hanging on the side of the room near the door. More white shirts flanked it on either side.

Written on the front of the shirt is the name of a girl I will never forget.

Annie Adair White was 16 when she was shot and killed by her ex-boyfriend, Gabe Dye, in her front yard after school. Dye then turned the semi-automatic handgun used to kill Annie on himself.

In 2010, I was a junior in high school. Like all juniors in high school, I was young, dumb and naive about the world around me. Then my friend was shot and killed.

My view of the world was dramatically changed on that October day.

Annie and I had known each other since I was 12. We were both in a group called the International Order of the Rainbow Girls — funny name, real mission. The IORG sorority is for girls ages 11 to 20 and encourages leadership through service and giving back. The members of IORG are, quite literally, sisters. We are a band of friends from all across the state. I may have been from Bismarck, and Annie may have been from Williston, but — as anyone who’s been in a sorority or fraternity knows — we shared a unique relationship.

In the days after the crime, The Bismarck Tribune would report that Annie came from a large extended family, was well-liked and was active in the fine arts. Dye was in the Math Olympics and other academic extracurriculars; the Tribune reported he was a nice guy.

When Annie was the victim of heinous crime, I was 16 years old and president of the Bismarck IORG assembly. One of the worst things I’ve ever had to do is call up girls, some as young as 11, and explain to them what had happened to their role model and friend. The mingled sadness and confusion that filled their voices when they understood exactly what had happened has ingrained itself deeply into my memory. Eleven-year-old kids should not have to understand what domestic violence is.

But they do. So many do.

Far too many.

If you want to see just a portion of how many kids and women and men and people have been impacted by violence, abuse, sexual assault, rape, incest and so much more, take a walk through The Clothesline Project.

Take a very long, short walk.

On Monday, I stopped and stared at the front of Annie’s white shirt, then walked around — past many more — to the other side. On the back of the shirt is a poem that says so elegantly and simply what those who knew Annie have been trying to put into words since October 18, 2010:

“She was that kind of girl/the one we will miss.”

Carrie Sandstrom is the editor-in-chief of The Dakota Student. She can be reached at [email protected]