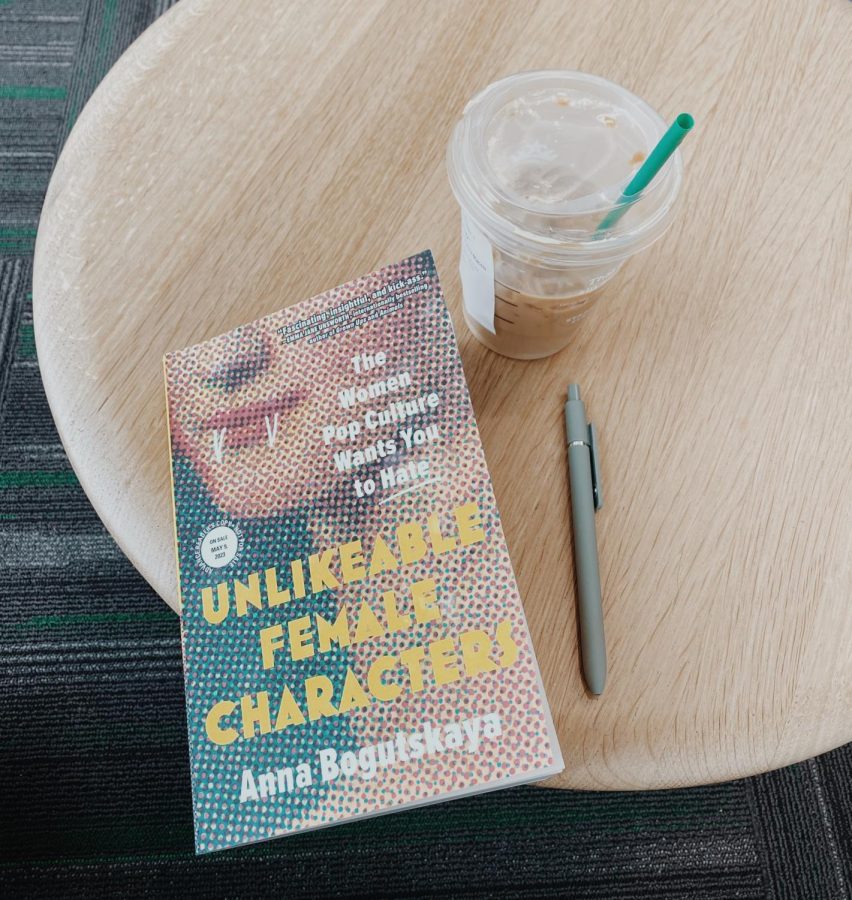

“Unlikable Female Characters”

Anna Bogutskaya Boom Review

April 19, 2023

Anna Bogutskaya’s debut book takes a deep dive into the archetypes of nine unlikable female characters. As a staple in the film industry, Bogutskaya uses her knowledge and experiences to shed light on pop culture’s obsession with female likability. This was an amazing dissection of how we view and portray women on screen.

The beginning of the book starts with the author’s own reflections on how books, movies, music, and pop culture shaped the way she understood both girlhood and womanhood. Her point being that women and girls are forced into behavioral boxes, and if they step out of those boxes, they must be punished, usually violently. This is then followed by a quick but very informative history of Hollywood and “unlikable” women’s place in it. The real meat of the book is found in the nine-character studies she does of archetypal unlikable characters. Her close reading of the example movies and characters, how these characters reflected pop culture, and the actresses’ reputation is not only an amazing use of film criticism, but also cultural criticism.

Bogutskaya does a wonderful job of analyzing these characters, th3 public perception of them, and why we seem to react to them the way we do, with unending empathy and understanding. She relates common shared experiences among women to these characters and how real-life experiences are shaped by what we watch in media. During much of her analysis, she reflects on her own teenage experiences. In her chapter on “the weirdo” she writes, “it [“The Craft,” 1996] holds the persuasive power of being extremely specific and totally universal at the same time, which is, in a way, what it feels like being a teenager. Your experiences are of a seismic magnitude; things considered small from an adult perspective feel end-of-the-world huge” (283).

It is with this nuance that she approaches all the character types she writes about. Her specific examples, including characters like Skylar White, Amy Dunne, Regina George, and many more, shed light on how small things eventually build up and spill over into the real world. The punishment of unlikeable female characters on screen encourages the punishment of “unlikeable” women off screen. From stereotypes of bitchy, ambitious women, mean girls who are nothing more than a pretty face and shrill women who just will not shut up, Bogutskaya approaches these women with an understanding that few are afforded. All these stereotypes are nothing more than excuses to ostracize real women, and that critique resounds throughout the whole work.

She emphasizes how women, predominately the actresses, and female characters are often used as moral compasses for pop culture. While men can be anything and be celebrated for anything, women must remain in their cultural and moral boxes. Instead of asking “is this an interesting character?” and “do they add value to the story?” female characters are faced with “are they likable? and are they good role models? and is their bad behavior punished enough?” Placing these unlikable female characters next to their very unlikable male counterparts, such as Walter & Skylar White, Tony & Carmela Soprano, Nick & Amy Dunne, and so on, Bogutskaya holds up a mirror to public perception and demands that people explain how characters like Walter White, a murderous drug kingpin who sells meth to minors, is applauded, while Skylar White, an overworked housewife who is kidnapped and forced to help her husband’s drug dealing, is the cause for so much hate.

The damning and punishing of female characters reflect the misogyny that is still apparent in our culture. Women have always been forced into moral roles and used as examples of good and bad behavior. The bad is punished and the good is unattainable. The characterization and demonization of these nine archetypes is more than just an on-screen phenomenon; it mirrors very real attitudes towards women who are too much and revel in being too much. The author’s final call to action is the abolition of the term unlikable. The term and idea are a disservice to women, to culture, and to interesting storytelling. Likability should no longer be a part of the debate or the industry. Instead, the focus should be on creating characters that people want to watch. Bogutskaya’s conclusion calls back to her opening statements, “likability is a moral trap” (303), and it is a trap women should not have to concern themselves with anymore.

Aubrey Roemmich is a Dakota Student Section Editor. She can be reached at [email protected].