Simulating an emergence

Emergency response teams gather to simulate emergency scenarios at GFK

When I came to, I couldn’t see anything. I could smell the smoke, and hear others banging on the walls of the plane, screaming for help. But pitch black darkness surrounded me, and I feared I had been blinded. However, I heard someone behind me remove a wing exit, and turning around, I could see city lights, and a surge of relief at flashing lights and sirens approaching- help was on the way. My chest hurt, badly. I couldn’t move my legs, and my left arm seemed to be glued to my side. Suddenly, a beam of light shot through the smoky haze; a rescuer had opened the door.

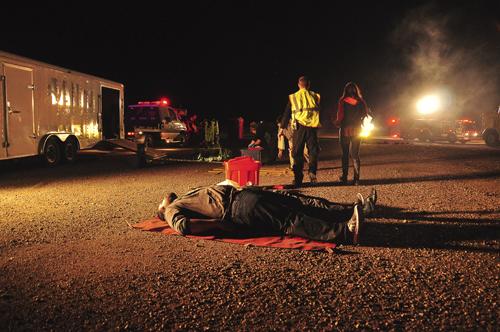

Those that could, rushed out of the airport, leaving us that couldn’t move. For several agonizing moments, firefighters moved up from the front, helping out those that were still alive. Finally, one got to me. I couldn’t speak due to the pain- I could barely breathe- and he had to support me down the aisle, and out of the airplane. Moving away, I could see a fleet of emergency vehicles standing by the wrecked plane, lights eerily flashing in the dark. I was dropped off at a triage unit. Help had arrived, and after a long wait on the cold ground, I was patched up, and sent off to the hospital with the other survivors.

At least, that’s what would have happened, had this been a real plane crash.

Last Wednesday, emergency response teams from all around the county participated in an exercise on the outskirts of Grand Forks International Airport. A total of 25 emergency vehicles, including two helicopters, were present at the drill, which the airport runs every three years, and although the airport initially asked for 75 volunteers, many more than that were present Wednesday night.

“This was definitely one of the biggest we’ve had in a long time,” Chris Deitz said. Dietz is the supervisor of the Airport Rescue and FireFighting Operations at GFK airport. Unlike the previous scenarios, which were daytime exercises, this was held at night.

Many of the volunteers at the exercise were students from the University of North Dakota; a good number of them were there for extra credit in different classes. As for myself, I had learned of the exercise through the Community Emergency Response Team, or CERT, that is based at the airport.

While I otherwise would have been at the accident as a responder, being a victim seemed a little more fun.

Victims of the “crash” were given cards that described their injuries- I had a “sucking chest wound” (a puncture of the rib cage that sucks in air), and the resulting blood stuck my arm to my shirt. We were then dressed up in gory makeup, and after several hours, sent to the plane to await rescue.

Once rescued, we were issued triage tags with four colors, green, yellow, red, and black. Green victims suffered only minor injuries, and were able to get themselves off the plane. Yellow victims had serious injuries, but they could wait to be treated, while red indicated a critical condition. Some yellow tagged victims, like myself, were later upgraded to red, as a result of exposure or other issues. If you had a black tag, your only destination was the morgue; those that were “dead” remained in the plane for most of the exercise.

In total, there were 126 passengers on our mock ill-fated flight; 17 died in the crash, one was airlifted to Altru via helicopter, and 21 others were taken by ambulance to receive “further treatment” (only 20 were assigned to be taken, but someone hitched a ride).

Victims arrived at the airport for preparation at 6 p.m., the exercise began at sundown, and by 11:20 p.m., the last Altru victims were back for sign out.

While we all walked away from this ultimately unscathed (aside from some sacrificed clothes), we left with a newfound respect for our emergency responders.

“You don’t really anticipate how much goes into a rescue like this,” student Connor Voeller said in an interview with the Grand Forks Air Force Base, “until you see it first hand with all the moving pieces that come together to make it successful.”

It’s disaster exercises like this that help train responders from all over the county and other towns, and while this catastrophe was planned, we can expect that those emergency crews will know what to do if the worst were to actually occur.

Connor Johnson is a staff writer for The Dakota Student. He can be reached at [email protected]